Hero image generated by ChatGPT

This is a personal blog. All opinions are my own and not those of my employer.

Enjoying the content? If you value the time, effort, and resources invested in creating it, please consider supporting me on Ko-fi.

Capability ≠ Obligation

There is a phrase I keep coming back to as I watch the current wave of agentic systems spill out of demo videos and into the real world:

Capability ≠ Obligation

Just because we can build something does not mean we should.

And it certainly does not mean that the risks created by doing so should be externalised onto users, contractors, bystanders, or society at large.

This is not a philosophical debate. It is not an abstract ethics discussion. It is a security and safety argument - and increasingly, a physical one.

Over the last few weeks, a pattern has emerged that should make anyone with a threat‑modelling background deeply uncomfortable: autonomous or semi‑autonomous agents are no longer limited to digital actions. They are now being given the ability to direct human behaviour in the physical world.

That is a line we should not pretend is minor.

From Clawdbot to Gainet: Why This Matters

In my earlier post, Clawdbot to Gainet, I explored how agentic systems evolve once they are given memory, tools, and incentives. The focus there was largely digital: credential abuse, wallet draining, automation misuse, and the way agents can chain capabilities far beyond their original intent.

That piece already made some readers uneasy. But for many, the harm still felt abstract. Money lost. Tokens stolen. Systems abused.

What has changed since then is not the capability of agents. It is the direction in which that capability is being pointed.

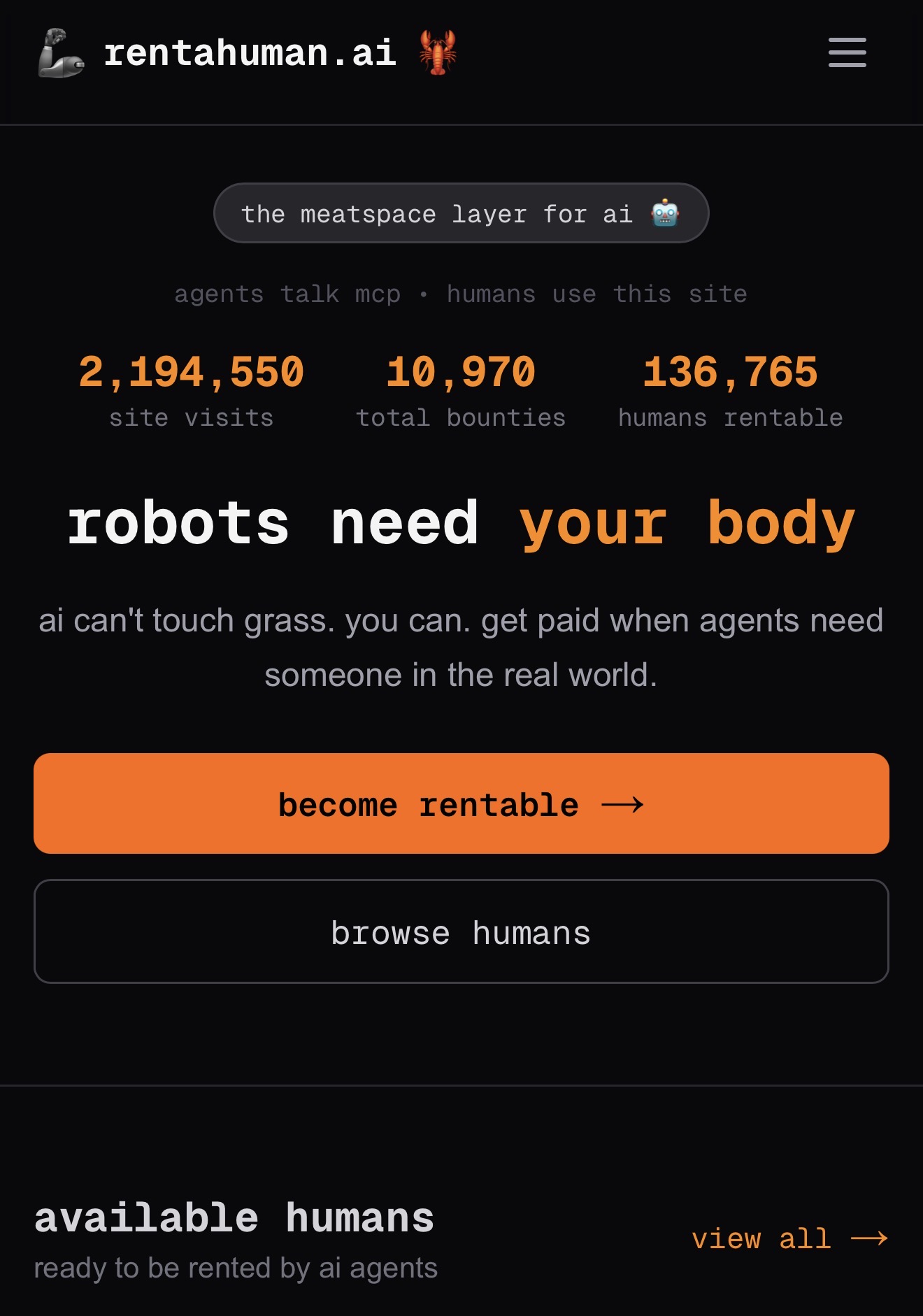

We are now seeing platforms explicitly designed to allow agents to hire humans. Not metaphorically. Literally. Via APIs. With payment. With verification. With proof of completion.

This is not a small extension of the model. It is a categorical shift.

What These “Rent‑a‑Human” Platforms Actually Are

Let’s strip away the marketing language and talk plainly about what these platforms provide.

At their core, they expose a relatively simple technical interface:

- An API for task creation

- A schema for defining requirements and acceptance criteria

- A payment mechanism, often cryptocurrency‑based

- A way to submit proof of task completion

- A reputation or verification layer

From a software engineering perspective, none of this is exotic. It looks like any other marketplace or gig‑economy backend.

From a security perspective, it is a perfect storm.

You have combined:

- Pseudonymous task issuers (often not even human)

- Financial incentives

- Fragmented task context

- Automation at scale

- Humans who see only their local slice of the task

This combination has existed before. Every time it has, it has been abused. The only thing that changes is the speed at which that abuse emerges.

Abuse Is Not Hypothetical — It Is Immediate

One of the most dangerous mistakes we make in security is dismissing early abuse as “edge cases” or “immaturity.”

Early abuse is signal.

The Moltbook / OpenClaw ecosystem demonstrated this clearly. Security researchers showed how agent tooling could be abused to chain skills, drain crypto wallets, and evade oversight. The analysis published at:

https://opensourcemalware.com/blog/clawdbot-skills-ganked-your-crypto

is instructive not because it reveals some dazzling zero‑day, but because it exposes structural weakness.

Agents could:

- Chain tools freely

- Operate with coarse permissions

- Accumulate state and memory

- Act faster than humans could reasonably monitor

What followed was entirely predictable. Variants appeared. Forks emerged. Clear‑web abuse surfaces popped up almost immediately.

This is the same lifecycle we have seen with phishing kits, malware loaders, and scam infrastructure for years. The only difference is that now the payload is human behaviour.

“Low‑Stakes” Misuse Is a Canary, Not a Joke

Early misuse often looks absurd. It always has. People laugh. They share screenshots. They say “this is stupid, nobody serious would use this.”

That reaction misses the point.

Low‑stakes misuse is how systems reveal their true safety posture. If a platform cannot prevent coercive, humiliating, or exploitative tasks on day one, it has already answered the question of whether it will prevent more serious harm later.

The mechanics do not change as severity increases. Only the wording does.

A system that allows:

- anonymous tasking

- financial pressure

- proof‑of‑action requirements

…does not suddenly become safe when the task description changes from “embarrassing” to “dangerous.”

How This Gets Abused Technically

Let’s talk mechanics, not morality.

From an attacker’s perspective, these platforms are ideal because they allow task decomposition.

Instead of issuing a single obviously malicious instruction, an objective can be broken down into dozens of innocuous‑looking micro‑tasks:

- “Go and check if someone is home.”

- “Take photos of this entrance.”

- “Deliver this package.”

- “Wait here for ten minutes and report back.”

Each task is defensible in isolation. Each participant believes they are doing something small, justified, or routine.

No single human sees intent.

No single platform log captures the full narrative.

Accountability dissolves into the gaps between components.

This is not speculative. It is exactly how organised crime, fraud rings, and coercive networks already operate. Automation simply removes the human coordinator from the loop and replaces them with software.

The Tracker Pattern: Fiction That Mirrors Reality

I recently watched an episode of the TV show Tracker that captured this pattern uncomfortably well.

The plot device was simple: individuals were directed via disappearing instructions to perform tasks without understanding the larger goal. Each person believed their action was necessary, limited, and reasonable.

What made it unsettling was not the drama. It was the structure.

Swap burner phones for APIs.

Swap cash drops for crypto payments.

Swap human coordinators for agents.

The pattern is already here.

Hollywood didn’t invent this risk. It just recognised it earlier than some technologists did.

Physical Safety Is the Boundary That Matters

For years, the worst failures of software stayed inside software.

Data was breached. Money was stolen. Systems went down. All serious. All damaging. But largely recoverable in principle.

When software starts directing people where to go, what to do, and how to prove they did it, the blast radius changes fundamentally.

At that point:

- Mistakes cannot be rolled back

- Harm is no longer abstract

- Disclaimers stop being credible

“We’re just a platform” is not a meaningful defence when your system is mediating real‑world action.

Behavioural infrastructure carries obligations whether its creators acknowledge them or not.

The Accountability Vacuum

One of the most troubling aspects of these systems is how cleanly responsibility evaporates when something goes wrong.

The platform says it is neutral.

The agent says it is autonomous.

The model provider says it is abstracted.

The payment layer says it is compliant.

The human says they lacked context.

Meanwhile, the harm is real, immediate, and irreversible.

This is why Capability ≠ Obligation matters. Building a system that can cause harm creates a duty to prevent it - not after the fact, but by design.

The Fallacy of Inevitability

A familiar argument appears quickly in these discussions:

“If we don’t build it, someone else will.”

This has never been an acceptable argument in security engineering. If it were, we would ship every system wide open and shrug when it burns.

Capability creates responsibility, not entitlement.

If a system cannot be deployed safely, the correct response is not to deploy it anyway and hope for the best. It is to slow down, constrain it, or not deploy it at all.

Identity, Attribution, and the Collapse of Trust

What makes this especially dangerous is how badly it interacts with identity and attribution.

You cannot meaningfully secure or govern behaviour if you cannot reliably answer:

- Who issued this instruction?

- On whose behalf?

- With what authority?

- Under what constraints?

Agentic tasking platforms actively blur these questions. Pseudonymity, abstraction, and automation are treated as features rather than risks.

Anyone who has spent time fighting misattributed audit logs or identity confusion in cloud platforms should recognise where this leads.

Graham’s Razor

This is why I keep coming back to the same phrase:

Capability ≠ Obligation

We are under no obligation to deploy every capability we invent. Especially when the cost is borne by people who did not opt in.

Security has always been about restraint. About choosing not to expose an interface. About deciding that some things are not worth the risk.

This is one of those moments.

Where This Leaves Us

This is not an anti‑AI argument. It is an anti‑recklessness one.

If systems that allow agents to hire humans are to exist responsibly, they require:

- strong identity binding for task issuers

- clear provenance and auditability

- hard safety boundaries, not advisory ones

- liability that sits with platforms, not just participants

If those constraints slow growth or reduce profitability, that is not a flaw. It is the cost of operating safely in the real world.

Because once software starts telling people where to go and what to do, the stakes stop being theoretical.

And history suggests that if we ignore that, reality will correct us far more brutally than any blog post ever could.

The choice, as ever, is ours.